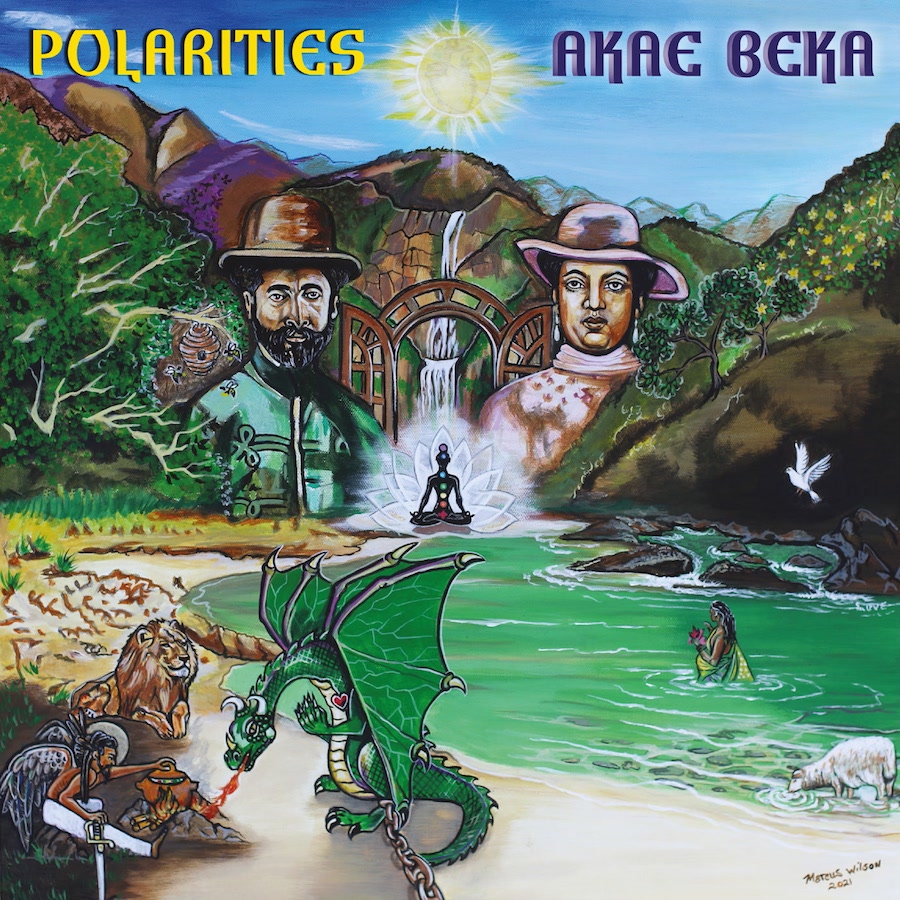

Akae Beka – Polarities – Review

Akae Beka Polarities Album Review by Mr Topple for Pauzeradio.com.

The late Vaughn Benjamin’s (Akae Beka) final project with I Grade Music has been highly anticipated. It is entirely worth the wait. Because it is nothing short of a moment in history.

Akae Beka Polarities, released via I Grade Music, is the final work from Benjamin and Tippy I Grade with Zion I Kings, as a collective. I Grade, who co-produced and was also responsible for the pitch-perfect mixing and mastering, is referred to in this review as part of Zion I Kings. And to say the album is revelatory may be an understatement. Because this miraculous record is life affirming and changing in equal measure. There’s no need to comment on quality – as this is Benjamin and Zion I Kings; so, it’s undisputed. But the overall content of Polarities is simply stunning.

It opens with Don’t Feel No Way; setting the stylistic tone for the whole album but also a thematic one – as the track is fairly upbeat and bright, like the sun shining through fair-weather clouds on a breezy day. It is classic Benjamin/Zion I Kings with production also from Andrew ‘Bassie’ Campbell: rich and lustrous in structure and with some gorgeous, delicate touches throughout. The rhythm section is Roots in its formation; a musical theme which is central, albeit with degrees of variation, to the entire project. But the influences of Soul also resonate; again, something which permeates Akae Beka Polarities.

Laurent ‘Tippy I’ Alfred’s keys run a bubble rhythm with a slightly staccato finish and little variation/syncopation from this, giving the track that signature, offbeat momentum. The bass from Campbell is fluid and smooth, avoiding too much picking and running a double-time rhythm based around arpeggio (broken) chords. It employs that classic Roots drop-beat arrangement, but only on beat three of the second bar of its two-bar phrase. This is a smart use of that old skool device, as it maintains a forward motion but still with the classic Roots intake of musical breath. Then over on the drums, and Tyrone ‘T-Rock’ Davis avoids a straight one drop: hi-hats perform an offbeat then quaver rhythm; the snare hits the two and four but the kick stubbornly refuses to follow suit, instead concentrating on the downbeats. At the end of every fourth bar delicate flourishes occur, shifting the hi-hats from closed to open and with rolls on the snare. Alfred is then back on the rhythm guitar, tripping a delicate skank just out of earshot. Overall, the rhythm section’s arrangement avoids the sluggishness of traditional Roots, instead employing techniques which give the feel of the genre but while maintaining momentum.

Don’t Feel No Way then has a plethora of other instrumentation. Balboa Becker’s trombone and Garrett Kobsef’s saxophone weave in and out; sometimes in harmony, at others running their own, graceful lines. The attention to detail in both artist’s performance is high; of note being the expertly executed dual crescendo/decrescendo and staccato/legato variation, with both performed precisely with each other. Padraic Coursey’s electric guitar line is subtle but effective. It sounds like it has the treble on the amp wound down a notch, as the tone is warm and slightly dampened. Alfred also gives a gently arranged and executed electric organ line, which runs a graceful countermelody. But from nowhere towards the end of Don’t Feel No Way enters Andrew ‘Drew Keys’ Stoch’s Rhodes piano. He performs a glorious solo bridge at the end, seemingly improvised and drenched in Funky Soul: dropping in blue notes, performing rapid runs and overall giving the instrument an almost vocal quality. The sum of these parts is an expansive, intricate composition which gives Benjamin a complex backdrop to work with. He focuses on his ability to deliver a Soul-led performance: full of intricate melodic detail, delicate vocal runs and some expertly executed backing vocals which interplay with his main line. He employs a rich palette of rhythmic patterns, too – and here excellent use of dynamics to drive home the exquisitely crafted message. It’s a glorious opener and an instant classic.

Next, and Charges switches the Roots sensibilities up – feeling like a musical summer rain shower; lightly glistening because off in the distance the sun still shine. Here, the rhythmic focus is on a one drop. David ‘Jah David’ Goldfine’s bass leads this, missing the first beat of every bar (and at times the two as well) and then running a semiquaver/quaver riff which uses that post-Rocksteady style of its own melody (versus Don’t Feel No Way’s broken chords). Goldfine’s style here is more picked and staccato – changing the feel of Charges entirely. But interestingly, Lloyd ‘Junior’ Richards’ drums don’t join in with the one drop. Instead, the kick again hits those downbeats while hi-hats double-time it and the snare focuses on the ups – with some military-style rolls at the end of phrases. Alfred’s keys run a bubble rhythm that is engineered to a lower dB than on Akae Beka Polarities’ opener, while a guitar compliments this with a skank. All this gives Charges a lighter, airier feel – which enhances the additional instrumentation perfectly.

Central to this is Stoch’s Rhodes piano. It’s a fairly constant feature, running rapid glissandos and riffs in the spaces between the main vocal line, and chords in the background. Then, enter Andrew ‘Moon’ Bain’s lead guitar to perform an interplay with this at points. There are some delightful synths – and overall, Charges is a light, somewhat ethereal track; the fairly detailed instrumental lines being elevated by the use of just three chord progressions on repeat throughout. Benjamin is then slightly different again, here focusing more on the rhythmic stanzas utilising dotted notation heavily and to good effect. He pares back the melodic diversity; makes notes shorter and more clipped on the verses – but extending them on the chorus. But his tone here is more purposeful and forthright, matching the devastating lyrics well.

The track Raining Thugs sees Zion I Kings bring some musical mimesis into play. But importantly it also serves as a musical/thematic marker for the shape of how the rest of the album unfolds. Roots devices once more pervade the track; for fear of repetition, listen closely and see if you can spot them. Because central to the overall feel of Raining Thugs is the additional instrumentation and production. Richards’ djembe and a balafon-type instrument sound like raindrops gently tapping on your windowsill: persistent yet mesmerising with their varying pitch but rhythmic persistency. But his rolls and rim-clicks on the snare feel like those raindrops are getting heavier. And then, synth horns are introduced for the first time on Akae Beka Polarities: rasping like the high-pitched first claps of thunder reverberating menacingly around your ears. Soon, Andrew ‘Moon’ Bain’s skanking rhythm guitar is doused in reverb, like the ever-distancing echo of the synth horns initial thunder claps. Eventually, Andrew “Bassie” Campbell’s kette come in, like the low rumbling of thunder retreating into the distance. And finally, Stoch’s Rhodes piano’s glistening crotchet chords are like the shimmering, slower falling of rain once the storm begins to subside. It’s a truly magical musical mimesis that carries you off into the turbulent and ever-changing weather it’s representing. For the whole album, it represents a heavy shower before something darker and more foreboding takes hold. Then, Benjamin provides the vocal and lyrical storm to match. He feels mournful yet incensed across Raining Thugs – stepping up the rhythmic intricacy with rapid-fire verses which here focus more on singjay than straight vocal. But on the chorus he breaks out into a full-on Soul performance, with some glorious riffs and improvisation to boot. It’s an infinitely clever track whose mimesis fits the lyrical content wonderfully.

One of two collabs on Polarities is Black Carbon with the pioneering Chronixx; musically feeling like the clouds of Raining Thugs haven’t quite cleared. Again, the rhythm section focuses on Roots: keys on a bubble rhythm; Goldfine’s bass on a varied riff (a beat two drop on bar one, and a one drop on bar two); Richards’ drums on a persistent, lazy rhythm and a guitar doing a subtle skank. Synth horns also run smooth, slow refrains, as does an orchestrated synth string section. But here, the additional instrumentation is varied and fulsome in its arrangement, moving the track into almost North African territory (with its Middle Eastern influences). Central to this is Sheldon Bernard’s flute. He performs a solo line which immerses across the whole track, weaving in and out of Benjamin and Chronixx’s vocals. Sounding heavily improvised, Bernard employs quarter-tone notes (those sounds between the usual 12-note, Western chromatic scale) which are endemic of MENA music. His rhythmic arrangement is particularly interesting, with dotted notation and triplets intermingled around the straight notes. Then, a kora from Mamadou Sidiki Diabate is also included – working a frantic accompaniment. Just to finish off the fascinating instrumentation, David Pransky brings a mandolin into the fray – bouncing off Diabate’s kora in an almost call and response formation. Then, Benjamin and Chronixx finish off this intensely ancient-feeling vibe with a glorious duet: both at the peak of their powers as they lament the highly intelligent nature of the lyrics. Their voices are perfectly matched: Benjamin working lower down his register while Chronixx focuses slightly higher up. It’s a poignant yet fascinating track, deftly executed by all involved.

Next, and Sow and the Reap begins more urgently than what’s come before it – avoiding that classic Roots drum introduction. Instead, it dives straight into a brooding arrangement of Roots-almost-meets-Folk-almost-meets-something else; not letting Raining Thugs and Black Carbon’s unsettling vibes leave. Parts of the rhythm section still focus on Roots: Bain’s guitar runs a skank; around a third of the way through Alfred’s keys join with a bubble rhythm, and Goldfine’s bass runs a drop-beat rhythm, skipping the third. Stoch’s trombone is also in keeping with Roots, running harmonised responses to Benjamin’s vocal calls. But the inclusion of Steve Katz’s acoustic guitar brings an entirely different feel to Sow and the Reap. He alternates between arpeggio and complete chords, as well as delicate melodic runs; almost Folk-like in its nature. But them, Zion I Kings have also brought in elements outside of these two genres. Heavy use of synths pervades the track, creating a modern Synthwave vibe. It shouldn’t work with the folksy guitar – but this being Zion I Kings, it naturally does. Benjamin steps his performance up a gear, again – working around a higher part of his register, raising the dynamics significantly and bringing in growls in his voice at points. His syllables are sharp and pointed; purposefully so – and overall Sow and the Reap feels like something violently simmering just underneath the surface.

Then, Royal Tribe moves Polarities’ sound further forward; offering a brief glimpse of the sun forcing itself through the dark grey, sullen clouds. While it is essentially a Roots track (bubble rhythm, check; drop-beat bass, check; skanking guitar, check) there are some new touches which Zion I Kings and Benjamin have included. For example, an almost Dancehall clave rhythm has been incorporated: that ‘oneeeeee-twooo-and’ beat split across the kick/snare and hi-hats. It’s subtle, but it’s there – and instantly brings a different type of momentum to the track. Gone is the direct forward motion, replaced by a slightly unsteady progression that winds from left to right as it moves forward; almost a musical representation of the lyrical content: “excitement in her wake, the entourage arrive”. Stoch’s Rhodes piano provides more momentum, by running semibreve chords at first before embellishing these with melodic syncopation. On occasion, the keys break off from their bubble rhythm with dotted syncopation and riffs. Additionally, a vibraslap marks the end of each four-bar phrase and the beginning of the new one. And, what sounds like a G-Funk whistle does pointed upward glissandos. Also, for the first time on Polarities, another artist provides the backing vocals: here, Fiona Robinson. Here, straight vocal harmonisation is the order of the day, and her rich and controlled voice sits perfectly with the bubbling composition. But Robinson’s appearance also ties-in to Benjamin’s performance. He exudes passion and awe in this instance, once again employing skilled vocal runs which are executed with the lightest of touches. He operates fairly pacey rhythms throughout and uses interesting melodic arrangement – often extending the same syllable across varied notes. It is gorgeous and pleasing in equal measure.

Everything Bless was one of the stand-out releases of 2020. You can read Pauzeradio’s full review of it here. In terms of the overall album’s construction, it feels like the sun has pierced through the meteorological darkness slightly harder – almost staving off the growing storm clouds. It’s delicately and intricately arranged, sympathetically produced by Zion I Kings and beautifully performed by Benjamin and Tiken Jah Fakoly – it’s a heartfelt and emotive Roots/Soul fusion, with nods to the Motherland as well. Credit must also be given to Diabate’s kora. Brilliantly performed, its full of light and shade – running rapid, complex runs across chromatic notes; the latter bringing a wonderful edginess when juxtaposed with the more soulful chord progressions (A flat root-minor fifth-major sixth). But the kora’s inclusion is of course a concerted link to Africa, too – encapsulating Everything Bless’s thematic content. Breath-taking and movingly gorgeous.

The pertinent and timely Viral Trend is in some respects the most musically pared-back track of Polarities up to this point. The track also feels like a turning point in the album – as from here the tone of the compositions change. Gone is Raining Thugs’ brief shower; replaced by an all-consuming, unbridled storm.

It also noticeably reduces the use of Roots musical devices. For example, drums do the first proper one drop of the album. But Viral Trend doesn’t want to emphasise that musical motif too much, as the bass avoids any kind of drop – hitting each beat on the head with syncopation in between. Then keys run a bubble rhythm. But at times they evaporate from this entirely, creating a feeling like the wind drawing back (with synth strings running breves like a pensive intake of breath), before the bubble returns like a growing gale returning. Meanwhile, there’s a delicious interplay between Stoch’s synth horns and his clavichord, varying in pitch and timbre as they run call and response patterns. And just here and there, Alfred’s organ runs heavily vibrato’d chords. But Zion I Kings have also brought in some elements of Dub, too. On the musical breaks, the remaining Roots device, the skanking guitar, has levels of reverb and decay added to make it sail off into the ether. Samples and additional synths are used intermittently to good effect; Benjamin’s vocal also has reverb washing across it and the breaks ultimately have their basis in Dub arrangement styles. But watch out for the end – as it smashes everything that’s come before it, moving into something entirely Funky Soul. Then, Benjamin plays to this arrangement well, here – working around an almost pleading tone, leaving a lot of space between certain stanzas as if almost pausing for thought, fitting in with the distinct musical breaks. He feels particularly emotive, here – which again marries with the heartfelt lyrical content. Superb.

Sing a New Song has a fascinating juxtaposition at its heart. When you read the title before listening to the track, you’d be forgiven for assuming it was an upbeat, positive experience. But instead, Zion I Kings and Benjamin have scored it all in a minor key; immediately creating a sense of near-despair – as does the very military opening, with its rolling snare arrangement. The chord progressions emphasise this, working from the root F minor, to the minor fourth and then major fifth. Roots devices are engineered more to the fore here, too – the guitar’s skank and keys’ bubble rhythm being most prominent, with the bass dropping beat four on the second bar of its phrase. Stoch’s clavichord returns more prominently, here, offering up a haunting countermelody as rasping synth strings wind around the track, often clashing with blue notes. His keys also break out of their bubble rhythm cage at times as Alfred’s organ also returns across those vibrato’d chords once more. Dub techniques also come back – breaks, reverb and some otherworldly use of synths all feature aplenty. Benjamin ups the ante of his imploring-laced performances, whining and weaving in and out of the unsettling music but paring back the melodic complexity perfectly to drive home the potent lyrics. But still, his signature Soul runs and riffs fit well – and the overall track is unnerving and thought-provoking in equal measure.

Next up, and Value Good Again continues Viral Trend and Sing a New Song’s more pensive and foreboding feel; again, scored in a minor key but with more intricacy than its two predecessors. To sum it up: the previous two tracks felt like the uncomfortable humid calm before a storm. Now here – it feels like the clouds are menacingly circling with the atmosphere brewing.

First off, and this unnerving feel is compounded by the use of just one chord progression across most of the composition: C minor (lasting a semibreve) to a crotchet of minor fifth then back to the root on the final beat of each bar. Once more, Roots devices are present – but like Viral Trend they’ve been arranged and engineered not to take too much prominence. Here, Alfred’s organ focuses on the bubble rhythm, but it has decay running in and out of each chord, creating rapid dynamic peaks and troughs. The guitars’ skank merges with this. But both cut away from these patterns at points, once more heralding musical breaks – with each instrument running riffs. Richards’ bongos patter away in the background juxtaposed against a main drum arrangement that’s more rapid than previously, with the hi-hats and snare creating semiquaver-led rhythmic phrase – while the kick sounds like it strikes every beat. Synth strings and other eery ones are back; Becker’s trombone and Kobsef’s sax are sparsely use, doing brief harmonic riffs and Noel ‘Scully’ Sims’ kette compound the brooding feel. The whole thing is deeply ominous – and Benjamin’s vocal serves to entrench this. He noticeably moves into a more sermonic, almost Nyabinghi style: firing the lyrics across unfussy melodies and rhythmic repetition. It is perhaps the most haunting of the album’s tracks – due to both the composition but also Benjamin’s mesmerising performance.

But then from nowhere come the title track; marking another shift in tone for the album with the ominous air beginning to clear. It’s opening sequence avoids any semblance of Roots entirely, causing you pause for thought: are we witnessing Funky Neo Soul across Polarities? Well, it soon settles into something near to Roots – with the usual musical suspects in play (bubble rhythm/drop-beat bass and skanking guitar). But there’s distinct ambiguity with this. The chord progressions here are detailed with a key-shift on the bridge; putting you in mind of something nearer Soul. Richards’ drums avoid Roots, instead having the kick heavily leading (not outweighed by the bass) on the downbeats, with an additional strike on the offbeat after the three. This complements the snare working on the two and four, while hi-hats run quavers. The arrangement plus the riffs at the end of every fourth bar give Polarities drum line the feel of Hip Hop. Then, Alfred’s organ runs striking, vibrato’d chords. But the other instrumentation puts you in mind of 80s Synthwave: dystopian, yet neither ethereal nor ominous. That delicate, bell-like synth piano sound drenches the track with its droplets of notation; a heavily wah-wah’d guitar with a pained vocal-like quality from Padraic Coursey comes to the fore towards the end, and some classic synth sounds (like a spaceship gun firing) just cement this dystopian vibe. If you were to try and box this in, then it would be as modern Neo Soul: the smashing up of various genres to create a wholly unique sound; check Nattali Rize’s Worldwide Rebellion for similar. Benjamin is stunning throughout, reverting away from Value Good Again’s chant-like approach, coming back to his Soul-style vocals with ease – and gives a performance filled with grace and feeling – but also an air paradoxical resignation. Given the lyrical content, it is truly moving and fitting of being the lead track.

Resonance marks a further tone change – moving into something lighter and more uplifting. It’s chord progressions (C major root-A sharp minor seventh and occasionally to the major seventh thereafter) almost put you in mind of old skool Dancehall; obviously it’s otherwise not near this. Alfred’s organ does the bubble rhythm, a guitar skanks but Goldfine’s bass doesn’t get involved with the Roots sensibilities, operating a winding, syncopated rhythm that hits every beat. But the Roots elements are almost secondary. Drums are persistent, but with some intense rolls on the snare and tom-toms at the end of each bar. Alfred’s clavichord almost sounds like a wah-wah’s guitar as it works around its lower register. Then, Bernard’s flute is almost a secondary vocal line – using those quarter tone notes again as it soars around Resonance, weaving in and out with deft improvisation. Becker’s trombone and Kobsef’s sax riff at points and some Dub engineering is occasionally brought in (sudden, elongated reverb for example). To try and musically box this Smorgasbord in is almost impossible; suffice to say you’d be forgiven for thinking it was almost a 21st century version of traditional Nyabinghi – because Benjamin with his vocal effectively delivers a sermon, not a performance. Pointed, clipped and very, very forthright – he uses majority staccato notation across the verses barely changing the melodic form to create something sermonic and chant-like. It’s powerful and compelling in equal measure.

Akae Beka Polarities concludes with Imandment to Heart and brings the album full circle: the storm has cleared, leaving something rainbow-like, drenched in the sun’s incandescent rays that have a deep and welcome warmth, absent for so long. The track’s shift to a major key (with attractive B major root-major fifth-major sixth chord progressions) is the more obvious musical device creating this feel. Kirk Bennett’s drums also play a part. The kick focuses on the downbeats but also the final off, creating once more that sense of positive forward motion that has been absent for many of the previous tracks. The bass does a one drop, bringing relaxed breathing space in; also avoiding the four in the first bar of its phrase. This creates glorious space and a sense of relaxation. Strings seem less foreboding than previously, running chords on the offbeats, giving the feeling of a musical gentle breeze. Roots devices still pervade the track: notably a bubble rhythm and the skank of a guitar. Stoch’s clavichord runs a playful rhythm in its lower register; a G-Funk whistle does a duet with Bain’s electric guitar and the whole track is laced with elongated reverb. It’s a musically smart and attractive composition, allowing Benjamin to perhaps deliver his seminal performance: mixing chant-like verses across impressive degrees of rhythmic arrangements, while soaring into a full Soul vocal on the verses with those signature runs smoothly soaring around the music. It’s a wholly fitting closing to not only Polarities, but in some respects Benjamin’s life – displaying the full, colourful complexity of his abilities.

There’s no denying that musically, Akae Beka Polarities is of course top class, as you’d expect from Zion I Kings and I Grade. But the real genius comes in the musical theme and tone running across the album. The feeling of shifting weather, from fair to a shower to the fight between the sun and the clouds, to storm then finishing with a rainbow, is not mimesis in the sense that Polarities is representing the weather. It is because Benjamin’s lyrical narrative across the album ebbs and flows naturally in this way – and Zion I Kings have masterfully constructed the music to match this.

Benjamin is often compared to Bob Marley in terms of his foresight and philosophical musings on society and the planet. Here is no exception – to the point where it’s almost impossible to fully appreciate what he has constructed, even after repeated listens. It may be that these, some of his final thoughts before departing us, will be mulled over for years by those with the ear to listen. Also, as with Benjamin, much of it is subjective: he leaves it open to the personal interpretation of the listener to fully immerse themselves in, and deconstruct on their own terms, his messages.

But there is a clear pattern, here: a narrative with clear peaks and troughs – with Zion I Kings musically shaping the album throughout to match. Note that the following is broken down into its simplest composite parts.

Don’t Feel No Way discusses how, even after millennia of society being this way, those of us with faith and trust in Jah shouldn’t ‘feel no way’ to maintain that faith and focus; specifically Rastafari, its teachings and practices – even in the face of Babylon’s “visceral, bristling animosities against archaeology”; that is – the proof of things that the system tries to erase. Charges looks at the system in more detail, but with a central message at its core: that Babylon and its proponents create a “crumbling unity” in society; are charged with “assault and battery” against us all but then “hook up the positive with negativity” – and yet still, the system “took us for granted but saying don’t leave”. Essentially, Benjamin paints a picture of us all being in an abusive relationship with the system, and he’s crafted it expertly.

Raining Thugs deals with Babylon’s proponents, while Black Carbon juxtaposes this with some heavy references to science while delivering the central message that despite varied ethnicity, we all come from the same place, are made of the same things, and ultimately end up the same way. Sow and the Reap seems to debate those who buy into Babylon’s nefarious ways and the reasons why this isn’t ultimately compatible with a sustained society and planet. Then, Royal Tribe appears to be a spiritual love song on the face of it – but it also feels like a spoken snapshot of a moment in ancient history, regarding the arrival of a Queen. It also represents a break in the main narrative.

Viral Trend gets the overall theme back on track, using the use of a pop culture phrase to plead with society to ‘lift ourselves up again’ from the toxic recess we have allowed ourselves to fall into. Sing a New Song then takes this message one step further – with Benjamin once more imploring us all to change course as a species and individuals – and Value Good Again instructs us on what we need to on this paradigm shift: “compassion which is feeling when the people are struggling”; not least the governments that he repeatedly references.

But Polarities takes the album into a sentiment change. You get the overriding feeling of resignation from Benjamin that (to break it down) many cannot be saved from everything he has discussed before this point – and that Rastafari have to resolve this issue in their own way, while continuing on their righteous path: “all that defence among the polarities. The wave has the crest and the trough, waiting for the wave to be desolation and obsolete, the way the victory be the sweet”. Then, he appears to have resolved this internal conflict by the entrance of Resonance, giving a veritable Song of Praise but also a lesson in maintaining one’s faith in the face of everything that came before this point on Polarities.

Imandment to Heart resolves everything that’s come before it: with its poignant central message that “chaos theory – sit back, relax and love”; in other words, while the world may be a torturous place under Babylon’s hand, be safe in the knowledge that, as (for example) “refugees push off on the raft” there is a greater plan for those of us with faith – regardless of where our path in life may take us; so, try not to worry – everything will be OK. It is utterly poignant and moving, given the fact Benjamin has left us – and feels like the musical conclusion to his life.

It’s hard to sum up Akae Beka Polarities in one paragraph. Zion I Kings and I Grade have outshone themselves once more in terms of the quality of the compositions and arrangements, and production values. But at the album’s heart is the synergy that clearly existed between Benjamin and them – because the overall project feels like a complete literary work, put down to music – with a start, middle and end. It will surely stand as one of the greatest albums of the decade – and possibly go down as one of the most important of recent times.

Listen to Mr Topple’s radio show here: The Topple UnPauzed Show

Akae Beka Polarities review by Mr Topple (18th May 2021).